What Are The Differences Between a Will and a Trust in Canada: Key Legal Distinctions and Estate Planning Insights

Wills and trusts are two foundational tools in Canadian estate planning, but they serve different purposes and offer unique benefits.

A will outlines how your assets are to be distributed after death and appoints an executor to manage your estate, while a trust allows you to transfer and manage assets during your lifetime or after death, often providing greater control and privacy. Understanding the legal distinctions between these two instruments is essential for developing a comprehensive estate plan.

This article explores the main differences between a will and a trust in Canada, helping you determine which—or both—best suits your estate planning goals.

Overview of Wills and Trusts in Canada

You use wills and trusts as legal tools to manage how your assets are handled and transferred. Both play key roles in estate planning, but they operate at different times and serve different purposes. Your choice depends on how much control you want, your privacy needs, and the complexity of your estate.

Definition of a Will

A will is a written legal document that outlines how your property and possessions will be distributed after your death. It names one or more executors, who are responsible for carrying out your wishes. You can also use a will to name guardians for minor children and specify funeral preferences.

In Canada, a will only takes effect after death. Before that, you can change or revoke it at any time, as long as you are mentally capable. Once you pass away, your will must go through probate, a court-supervised process that confirms its validity and gives legal authority to the executor.

Wills can be typed or handwritten (holographic), depending on provincial rules. For instance, in Ontario, wills fall under the Succession Law Reform Act, while each province has its own legislation governing format and execution. A properly prepared will ensures your estate follows your chosen instructions instead of default provincial laws.

Definition of a Trust

A trust is a legal arrangement that gives one party, called a trustee, the authority to manage assets for another, known as a beneficiary. You, as the settlor, create the trust and specify its terms. Unlike wills, certain trusts—such as living trusts—take effect while you are alive.

A living trust allows you to retain control of your assets while simplifying how they are transferred later. For example, a living trust can help avoid probate and maintain privacy, since the document is not filed publicly. Some individuals prefer trusts when they own property in multiple provinces or want ongoing management for family or charitable reasons.

Trusts can be revocable or irrevocable. Revocable trusts let you change terms during your lifetime, while irrevocable ones generally cannot be altered. This structure gives you flexibility or protection, depending on your goals.

Legal Status in Canadian Provinces

Each province in Canada sets its own laws governing wills and trusts. These laws define how the documents must be written, signed, and witnessed. You must follow local rules to ensure your will or trust is valid. For instance, Ontario’s Succession Law Reform Act enforces specific witnessing requirements, while British Columbia’s Wills, Estates and Succession Act (WESA) allows electronic wills.

In contrast, Quebec uses the Civil Code, which has its own framework for succession and trusts. These differences mean a document valid in one province may need adjustments to apply elsewhere.

Provincial differences affect estate administration. Understanding these variations helps you plan effectively, particularly if you own assets or property across multiple provinces.

Key Differences Between Wills and Trusts

In Canada, you can use wills and trusts together or separately depending on how you want your property managed, when you want transfers to occur, and how much privacy you need. The main differences involve who controls the assets, when each document takes effect, and how easily you can change the terms over time.

Control and Ownership of Assets

A will directs how your property is managed after your death. You maintain full ownership and control over your assets while you are alive. Once you pass away, your executor manages and distributes the estate based on your instructions. The process usually goes through probate, which can delay distribution and make details public.

A trust operates differently. When you create a trust, legal ownership of the assets transfers to the trustee, who manages them for the benefit of your chosen beneficiaries. This shift in control can occur while you are alive or after death, depending on the type of trust. Unlike a will, a trust can keep assets private and avoid probate.

To understand why this control difference matters, note that trusts allow you to set ongoing conditions for how and when assets are used. For example, they can help manage funds for minor children or dependants with special needs.

Timing of Effectiveness

A will becomes effective only after your death. It has no legal authority during your lifetime, meaning your executor cannot act on your behalf until probate confirms the document. This structure makes a will suitable for distributing property once your estate has been finalized.

A trust, on the other hand, can take effect immediately once it is created. You can establish a living trust (also called an inter vivos trust) to manage assets while you are alive, or a testamentary trust that activates after your death. Living trusts can continue managing assets seamlessly, which can be valuable if you become incapacitated or wish to delegate management responsibilities.

This ongoing operation gives trusts greater flexibility in long-term estate management, reducing disruptions that might occur during probate.

Revocability and Flexibility

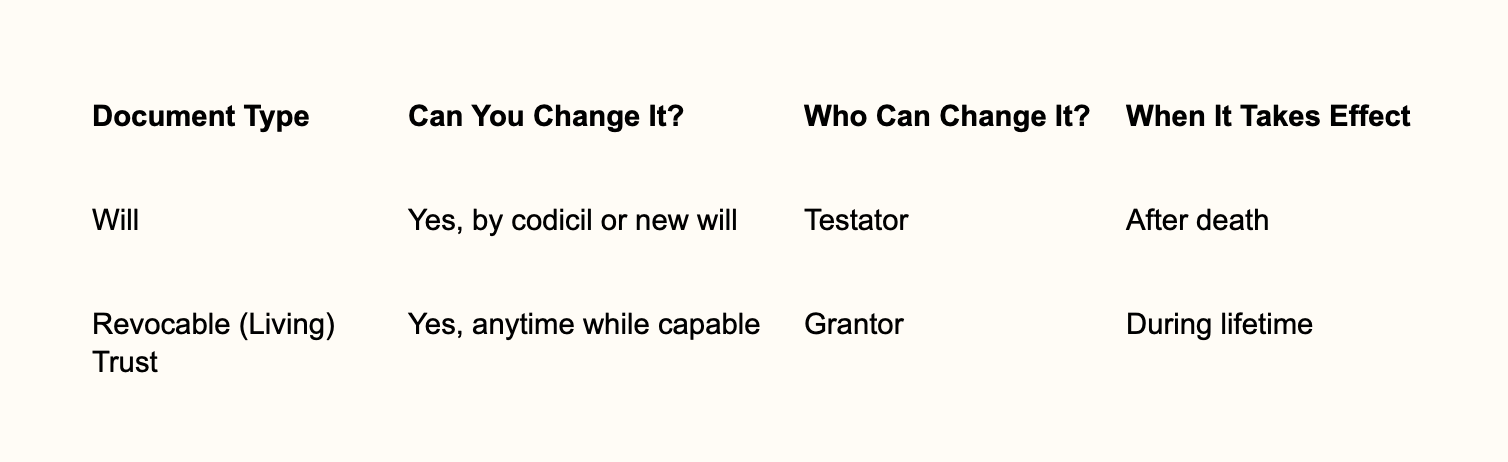

You can change or revoke a will at any time as long as you are legally competent. Common updates include adding new beneficiaries, removing outdated ones, or adjusting gift amounts. The ability to do this makes a will an adaptable planning tool. However, any amendment must follow legal formalities, such as witness requirements set by provincial law.

Trusts vary in how flexible they are. A revocable trust lets you modify or dissolve it at any time, giving you flexibility similar to a will. An irrevocable trust, however, generally cannot be changed once established, which provides more asset protection but less control. The level of flexibility you want should guide your choice between these trust types.

Use the table below to compare key points:

How Wills Operate in Canada

A will provides a clear legal framework for how your property and personal belongings are handled after your death. It must meet formal requirements under provincial law, appoint an executor to carry out your wishes, and list how your assets will be distributed among your chosen beneficiaries.

Formal Requirements

In Canada, each province and territory has legislation outlining how a will must be made to be valid.

Most provinces require your will to be in writing, signed by you, and witnessed by two independent adults. These witnesses cannot be beneficiaries or spouses of beneficiaries. In some cases, handwritten or “holograph” wills are accepted if clearly written and signed by you without witnesses.

Wills must also identify you by name, include the date of signing, and show your intent for it to take effect upon your death.

Role of the Executor

Your executor, sometimes called a personal representative, ensures your instructions are followed and manages your estate affairs. This person collects your assets, pays any debts or taxes, and distributes property to the named beneficiaries.

Executors must act honestly and in the best interest of your estate. They often need to apply to the court for probate, a legal process confirming the will’s validity and their authority to act. The court-issued “Grant of Probate” allows financial institutions and government agencies to release your assets.

Because the executor has significant responsibilities, many people choose a trusted family member, close friend, or professional such as a lawyer or accountant. Professional executors can be helpful for complex estates with property or business interests.

Distribution of Estates

A valid will directs how your estate will be divided among your beneficiaries. You can leave specific gifts, such as money or property, or divide your estate by percentage. You may also make charitable donations or set up trusts for dependants.

If you die without a valid will, provincial intestacy laws decide who inherits your property. This process can delay estate settlement and may not reflect your wishes. Using a clearly written will avoids most disputes and ensures your decisions guide the outcome.

In Canada, combining a will with other planning tools, like trusts, can strengthen your strategy for passing on assets. Wills remain the foundation of most estate plans, ensuring that all property not included in a trust or joint ownership is properly accounted for.

How Trusts Operate in Canada

Trusts in Canada function as legal arrangements that allow you to transfer property or assets to another person or entity for the benefit of chosen individuals. They follow specific legal rules that determine how the assets must be managed, who benefits from them, and how taxes apply.

Types of Trusts

Trusts in Canada fall into several main categories. The most common are inter vivos (living) trusts, created while you are alive, and testamentary trusts, which come into effect after your death through your will. Living trusts can include family trusts, alter ego trusts, and joint partner trusts, each serving unique purposes such as tax planning or estate transfer.

An inter vivos trust lets you transfer assets during your lifetime while keeping some control over how they are used. A testamentary trust, by contrast, is useful for supporting minor children or dependants after your death. These tools differ mainly in timing and flexibility.

Trusts can also vary in their tax treatment. Income earned in a testamentary trust is usually taxed at individual rates, while income in an inter vivos trust is taxed at the highest marginal rate. You should consult a financial or legal professional when deciding which type fits your estate planning goals.

Role of the Trustee

The trustee is the person or institution that controls and manages the trust’s assets. Under Canadian law, trustees have fiduciary duties to act honestly, carefully, and in the best interests of the beneficiaries. They must follow the trust document and cannot use trust property for personal benefit.

You can appoint one or more trustees. In complex estates, a corporate trustee like a trust company may be preferred for its expertise in managing investments and keeping records. Trustees must also handle tax filings, distribute income or capital as outlined in the trust deed, and maintain full transparency with beneficiaries.

Key trustee responsibilities include:

Managing trust assets prudently

Keeping accurate financial records

Reporting and paying taxes on trust income

Communicating clearly with beneficiaries

If a trustee fails to meet these legal duties, a court may remove or replace them.

Beneficiary Rights

Beneficiaries hold the right to benefit from the trust under the terms you establish. Their rights depend on the type of trust and the conditions set out in the trust agreement. For example, income beneficiaries may receive ongoing payments, while capital beneficiaries receive assets after specific events such as the sale of property or your death.

Beneficiaries have the right to information and accountability. They can request statements that show how the trustee has managed the assets and how much income or capital they are entitled to. In Ontario, trust law requires trustees to keep records accessible for review and to explain decisions affecting distributions.

This structure ensures that trustees act in good faith and beneficiaries are not left unaware of how their interests are handled. If a trustee fails in their duty or mismanages the trust, beneficiaries may seek court involvement to enforce their rights.

Succession and Probate Processes

In Canada, succession and probate rules govern how your property transfers after death. Each province manages these processes under its own laws, which determine whether your estate must go through the courts or can be handled privately. The structure of your estate plan—whether based on a will or a trust—directly affects how long and complex these steps will be.

Probate for Wills

A will usually requires probate, a court‑supervised process that confirms the document’s validity and authorizes your executor to act on behalf of the estate. Probate ensures debts and taxes are paid before assets are distributed. This process protects executors from liability if the will is challenged.

The probate process involves submitting documents, obtaining a grant of probate, and paying probate fees, which vary by province. Ontario, for example, calculates Estate Administration Tax based on estate value. When the estate includes real property or financial accounts, most institutions require probate before releasing funds.

Key points:

Court approval validates the will.

Creditors must be settled before beneficiaries receive assets.

Probate records become public, reducing privacy.

Small estates may avoid formal probate if financial institutions accept alternate documentation. However, larger or more complex estates almost always require court confirmation to ensure a legal and transparent transfer of ownership.

Avoidance of Probate with Trusts

A living trust operates differently from a will. When you place assets into a trust during your lifetime, they legally belong to the trust, not to you personally. Because ownership changes before death, these assets do not go through probate. This allows faster distribution and greater privacy.

The appointed trustee can manage and transfer assets according to your instructions without court approval. This process can reduce administrative delays that often accompany probate. Beneficiaries receive their inheritance directly from the trust, avoiding the public nature of court filings.

Advantages of using a trust:

Establishing a trust may involve higher upfront costs, but it can simplify administration and protect confidentiality for you and your heirs.

Privacy and Public Record Considerations

When you make a will, it becomes a public record once submitted to probate court. This means that details such as your name, the value of your estate, and your beneficiaries are open for public viewing. This lack of privacy can raise concerns for families who wish to keep financial and personal matters confidential.

A living trust, on the other hand, generally remains private. It does not go through probate, so the distribution of your assets and the identities of your beneficiaries are not made public. This privacy is one of the key reasons some individuals choose a trust over a will.

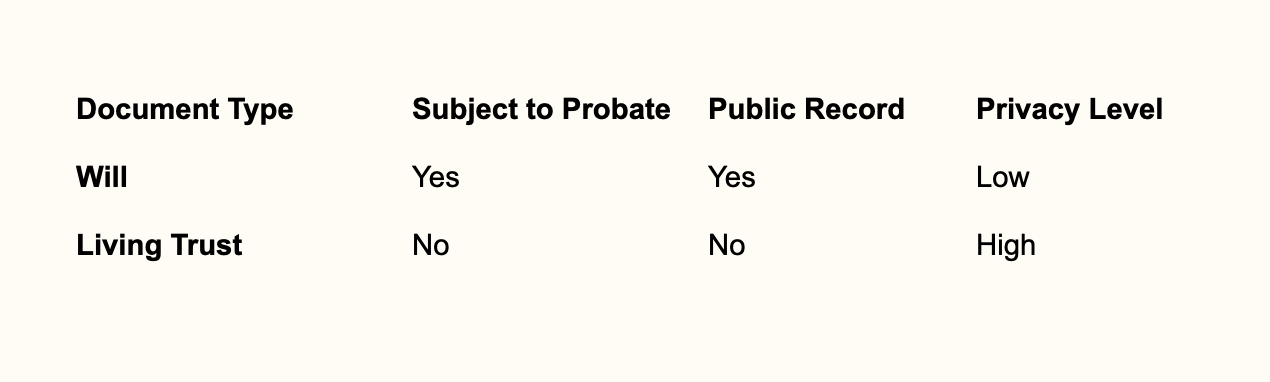

The table below highlights how wills and trusts differ in terms of public access:

You may prefer a will if your primary goal is to outline guardianship for minor children or handle smaller estates. However, if you value confidentiality or wish to avoid the public process of probate, a living trust may better suit your needs. Each option offers distinct implications for your privacy and your family’s access to information after your passing.

Tax Implications for Wills and Trusts

When managing your estate, it is important to understand how taxes apply to your assets and distributions. The Canadian tax system treats wills and trusts differently, which affects how much tax your estate or beneficiaries might pay.

Estate Taxes

Canada does not have a formal estate or inheritance tax. However, when you pass away, your estate faces a deemed disposition of assets at fair market value. This means the Canada Revenue Agency treats all capital property as if you sold it right before death. Any resulting capital gains are included in your final tax return, which can raise the estate’s income level.

For example, the sale of investments, real estate, or business shares can create significant taxable income. Registered accounts such as RRSPs are also fully taxable upon death unless transferred to a spouse or qualified dependent. Because of this, managing timing and ownership of assets is critical in estate planning.

Your executor must also file a final return and possibly additional returns for income earned after your death. These tax obligations can increase the cost and complexity of settling an estate, particularly one with multiple income sources or beneficiaries in different provinces. Effective planning may help limit these costs through charitable gifts or spousal rollovers.

Tax Treatment of Trusts

A trust pays tax on its undistributed income and is considered a separate taxpayer under Canadian law. Income retained in the trust is taxed at the top marginal rate, unless the trust qualifies for special treatment, such as a Graduated Rate Estate (GRE) or a Qualified Disability Trust (QDT). These two categories are exceptions that allow lower, graduated tax rates, unlike most other trusts which are taxed at the highest rate.

An inter vivos trust—created during your lifetime—is taxed each year on income it earns. Income distributed to beneficiaries is deductible to the trust and taxable to those who receive it. This allows some flexibility in allocating income to minimize overall taxes.

Testamentary trusts generally have fewer advantages than before, but can still help manage assets for minors, dependants with disabilities, or complex family situations. Trustees must file annual returns and maintain clear records to remain compliant with the Income Tax Act. This structure provides control and continuity, though it adds administrative duties and ongoing costs.

Costs Associated with Wills and Trusts

The cost of drafting a will in Canada is generally lower than that of a trust. A simple will commonly costs between $300 and $1,000 to prepare, depending on how complex your estate is and whether you use a lawyer or an online service. However, wills often lead to additional expenses later due to probate fees, which can range from 3% to 7% of the estate’s value.

A trust, especially an inter vivos or living trust, usually costs more to set up. Legal fees can rise due to the extra documentation and registration required. Trust creation often involves ongoing management fees, including potential trustee compensation and administrative charges.

While a trust avoids probate, it may involve higher upfront and maintenance costs. You should consider whether the long-term benefits, such as privacy and continued asset management, outweigh the initial expenses.

Amending or Revoking Wills and Trusts

You can change or cancel your estate planning documents, but the legal process differs between wills and trusts. A will can be revoked by creating a new one or by intentionally destroying the existing document. However, you must follow specific formalities set out by provincial law. For instance, to legally amend or revoke a will in Canada, you must comply with the requirements explained under provincial acts.

Creating a codicil, which is a written amendment to your will, lets you make updates without rewriting the entire document. You must sign and witness it in the same way as the original will. If you marry or divorce, certain events may also automatically revoke parts of your will.

A revocable trust, often called a living trust, offers more flexibility. As the grantor, you can modify or revoke it at any time during your lifetime as long as you remain mentally capable.

Proper legal advice helps ensure your amendments meet formal requirements and reflect your intentions accurately.

Selecting Between a Will and a Trust in Canada

When deciding between a will and a trust, you should first consider your estate’s size, complexity, and goals. A will may suit you if your estate is simple, while a trust can offer more flexibility for managing larger or more complex assets. Your financial situation and family needs play key roles in making this decision.

A will is often easier and less expensive to create. It lets you name beneficiaries, appoint guardians for minor children, and direct how your assets should be distributed. However, wills typically go through probate, a public legal process that validates the document and may delay distribution.

In contrast, a trust can help you manage and transfer property while you are still alive. Creating a trust lets you avoid probate and maintain privacy because the terms are not made public. Trusts can take effect during your lifetime, giving you greater control over how your assets are handled.

It may also be possible to use both tools together. Combining them can provide a balance between cost, control, and long-term security.

The Final Verdict

While both wills and trusts are valuable estate planning tools, they differ significantly in how and when they take effect, the level of control they provide, and their tax and privacy implications. Choosing the right combination depends on your financial situation, family structure, and long-term objectives.

For professional guidance in determining whether a will, a trust, or both are best suited to your needs, contact the attorneys at Parr Business Law. Our experienced team can help you design a comprehensive estate plan that protects your assets and honours your intentions.